Cheap power, using old school tuning techniques, tested on a dyno to separate fact from fiction.

Tuning components for Lambretta and Vespa scooters have never been in such plentiful supply if the fancy takes you and you have available funds… the array of shiny tuning-exotica is really quite astounding.

Enjoy more Scootering reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Vespa has always had the benefit of well-established tuning houses such as Malossi, Pinasco, Polini, and so on providing off-the-shelf kits, clutches, exhausts, carbs, cranks and more. Lambretta tuning has historically relied more on privateers and small home-grown companies to develop and release great kits like the Challenger, Avanti, AF TS1, MB Race-Tour, Gran-Turismo and so on. But in either case, Lambretta or Vespa, you can start spending as little as a few hundred pounds on cylinder kits, right up to five-figure sums on the really ‘high-end’ gear. Today’s budget choices are astounding, from twin-cylinder engines, to CNC casings, 305cc 51bhp Vespas and, potentially, a 60bhp 345cc Lambretta. The situation is wild and mind-boggling. Who ever thought we would see this level of tech for our beloved scooters?

It’s fabulous.

But tuning exotica and spending frenzies aside, what if we just want bang for buck? Suppose you just want more power per pound — how do you decide where to start? Where do you get the information to decide what works and what doesn’t? We are all aware of standard recommendations people make — fit a pipe, match your casings, enlarge your transfers, flow your manifold, fit a bigger carb, have it set up on a dyno etc. The list of advice from your mates down the pub can be bewildering. Everyone is an expert, everyone has an opinion, you speak to your local dealer who recommends A, but the bloke on the phone 100 miles way recommends B. Then, of course, this guy’s shop website recommends C, and that group of fellas on a forum recommended D. So a quick check on Facebook to canvas opinion, and everyone just swore at each other, had an argument about it all, and now you’ve no idea what to do.

Fear not the inquisitive mind of Darrell Taylor recently kicked into action again, and for no other reason than his own advancement of knowledge, Darrell purchased a bog standard SIL200cc Lambretta engine and set about finding what works and what doesn’t. Darrell ran through a set of basic and well-known tuning options in order to attain empirical data that defines exactly what can be achieved. The basic premise of the test was to advance a SIL motor in stages, testing at each point, and then moving on a step, as the results were recorded for each stage.

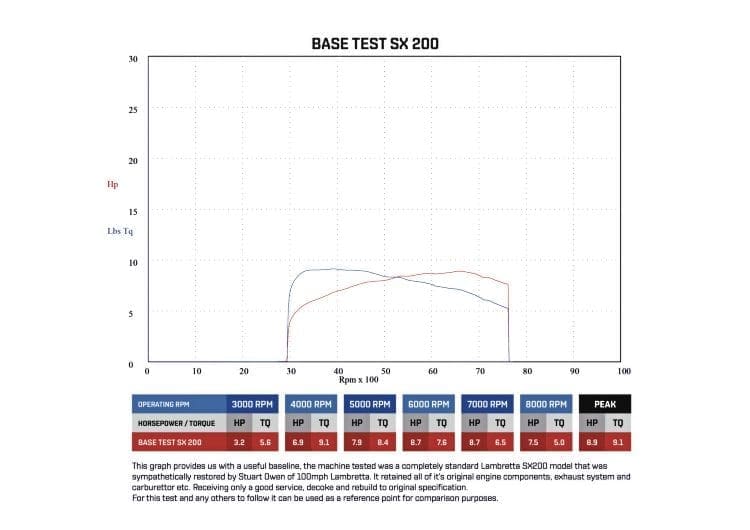

Base Test:

So the first thing to do was to set a base parameter — what is a commonly accepted figure for a standard 200cc Lambretta engine? I know from numerous tests on my own dyno that a standard 200cc Lambretta engine with clubman pipe, 22mm carb and an airbox will produce pretty much 9hp at the back wheel every time with only very minor variations between engines. And that information matches up to the first graph here, which came from a restored SX200 moto that had a full service and clean up, and maintained all original parts. Dyno results are: peak HP shown in red is 8.9 and peak torque shown in blue is 9.1

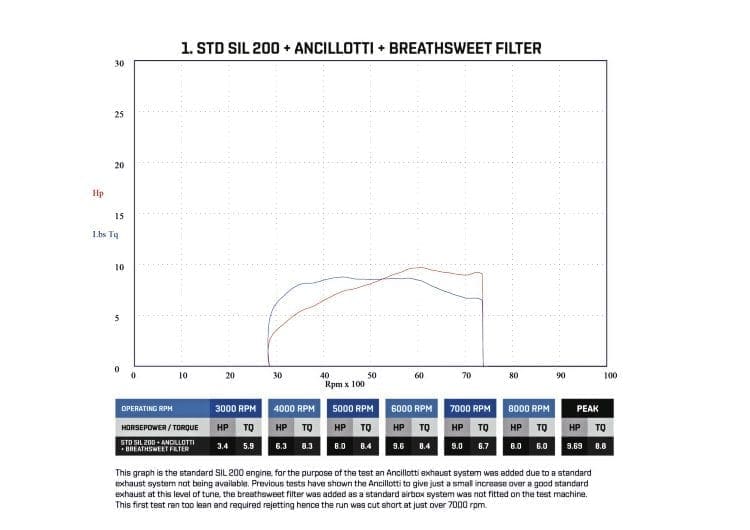

Step 1: These days a basic SIL engine is usually supplied without an exhaust, carb or airbox. So the first thing to do was fit those items. Darrell used a standard 22mm carb, an Ancillotti pipe and a 90-degree rubber elbow with breathsweet filter. However, the introduction of a breathsweet filter made the air/fuel ratio on the test motor run VERY lean. This is because a 90-degree rubber elbow and breathsweet filter increase air velocity and air flow significantly over a standard bellows/airbox system. Dyno results are: peak HP shown in red is 9.69 and peak torque shown in blue is 8.8

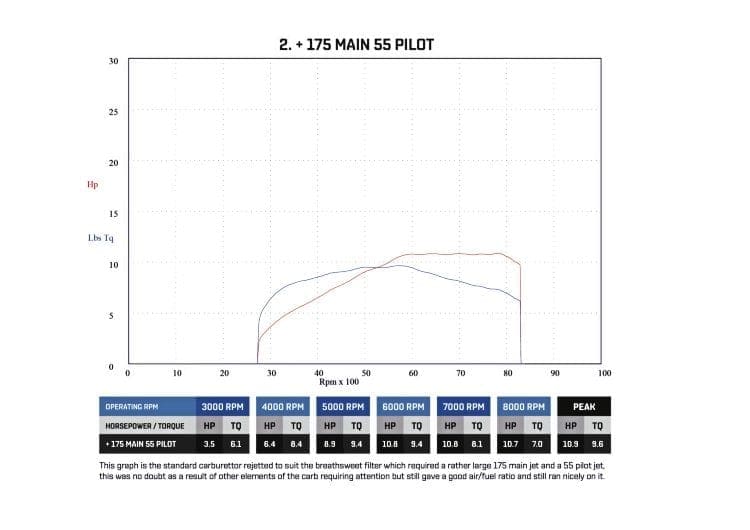

Step 2: After noting the lean air/fuel curve Darrell simply up-jetted the carb until he found a satisfactory 12.7:1 ratio. Starting from the standard jet size of 122 main and 48 pilot, which came with the carb, Darrell continued upwards until finally settling on a 175 main and 55 pilot, which shows just how lean the engine had been running before. The result was good and the engine loved the extra fuel. Dyno results are: peak HP shown in red is 10.9 and peak torque shown in blue is 9.6

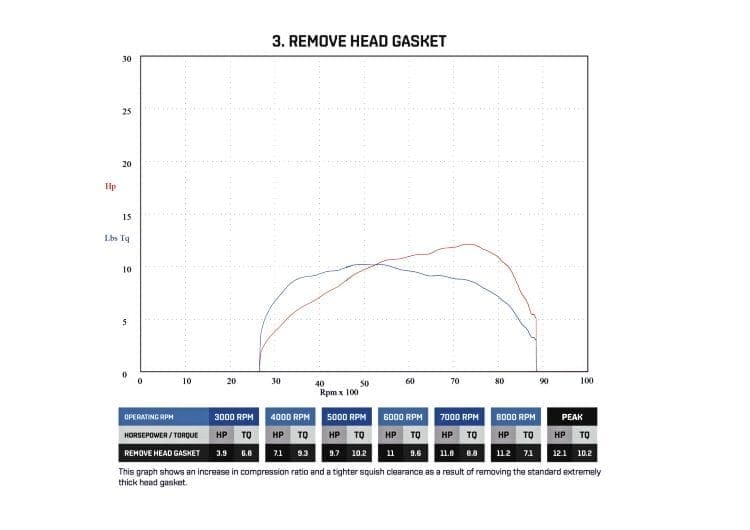

Step 3: So with good progress being made via the Ancillotti exhaust and filter system set up properly on the dyno, some extra measurements were introduced. The compression pressure of the top end was checked, and in current trim it came in at 80psi, which is a lower-scale reading. The squish gap was also checked and was found to be a staggering 2.6mm! So a very simple and effective test here was to simply remove the very thick 1.5mm head gasket and re-test. Predictably, the squish now measured 1.1mm, which is marginally tight for general road use, but very acceptable for the testing process and data gathering.

Compression pressure was re-checked with the gasket removed and had been raised to 103psi, which is much better. Time for the dyno to do the talking. The engine was run up once more. Dyno results are: peak HP shown in red is 12.1 and peak torque shown in blue is 10.2

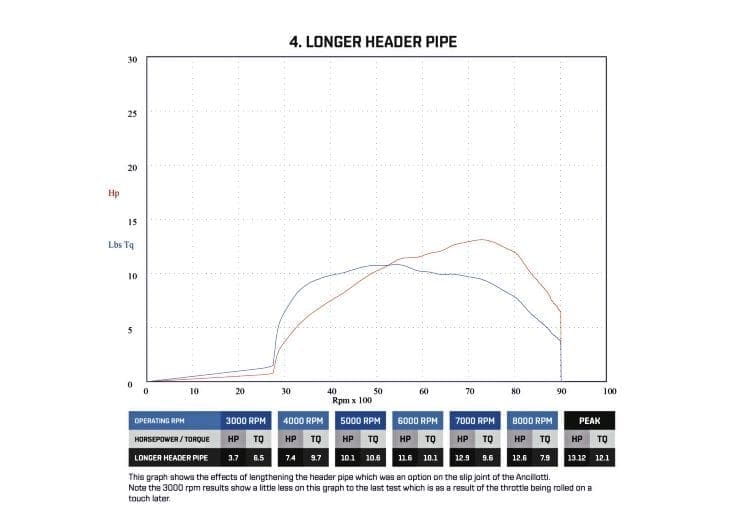

Step 4: So now things are making sense on the dyno, readings on squish and PSI are looking good and we are up around 30% on a standard machine. Time to play with the exhaust, a very easy and subtle test, but one that can throw up some interesting results.

Tuned lengths on exhausts are an important factor in two-stroke tuning, so by simply slackening the U-bend slip joint bracket and wiggling the pipe out to its maximum length, Darrell could gain over an inch of extra tuned length. Dyno results are: peak HP shown in red is 13.12 and peak torque shown in blue is 12.1

At this stage Darrell has taken a standard engine just about as far as any reasonable home-tuner/mechanic might be expected to emulate. The results are fascinating and show a staggering 45% increase over a standard SIL unit by focusing on some very straightforward features like pipe, filter, squish, compression and jetting. In terms of bang for buck, these results are extremely rewarding and encouraging. A machine like this, with the right gearing, could be a real mile munching machine, very sedate to ride, but with enough power to propel you around nicely.

A very helpful power chart to help you see the step-by-step changes in an easy to read overview.

So what next?

The obvious questions we need to know the answers to are what is the quality of a standard SIL200 engine like straight off the shelf? Are the components good enough to be reliable? And what if I want MORE power?

The obvious and easiest changes for more power are to remain with the entire unit as it stands for now, and try a bigger carb and a different pipe. So the 22mm carb was removed and replaced with a 26mm bored version, once the air/fuel readings were matched like-for-like, the engine was tested on the dyno.

The result from this test was very interesting— the fitment of a bigger carb showed almost no discernible power change at all, perhaps 0.2 of a horse-power at best. So the 26mm unit was removed and the standard size of 22mm refitted.

Does this mean that big carbs are a waste of money and do not work? Well no, it just means that the carb this unit has fitted is about the best size for the rest of the engine it is matched to.

However, later tests Darell has been investigating show where a big carb DOES work and gives the power increase that are expected, and that is something we will look at over the coming editions, along with a few other items.

Upcoming reports include:

- Fitting an expansion chamber, what power increases occur?

- Fitting a bigger carb, when is this the right thing to do?

- Clutches, how much power can a standard clutch handle, and what are my options if it starts slipping?

- Do mid-weight and light-weight flywheels make a difference? Which one should I choose?

- What are my options for porting a cylinder and piston upgrades?

These are some of the items we will be covering over the coming editions to answer some of your questions on how to get more power reliably and cheaply… bang for buck!

It’s not a definitive guide, as tuning is always a subjective topic, but we hope to put to bed come of the age-old myths and give you some hard facts on which to base your decisions.

One of the most important questions before we start on any of the above tuning options is what are the weak points of my standard engine? What should I be looking to upgrade on the basic unit? The answers to this are obvious in a couple of cases, but more than surprising in others.

Through road-testing and use Darrell has identified a series of weak spots and preferable upgrades, and that will be our starting point for next month’s editions. See you then.

Dan

This article was taken from the May 2016 edition of Scootering, back issues available here: www.classicmagazines.co.uk/issue/SCO/year/2016

Enjoy more Scootering reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Scooter Trader