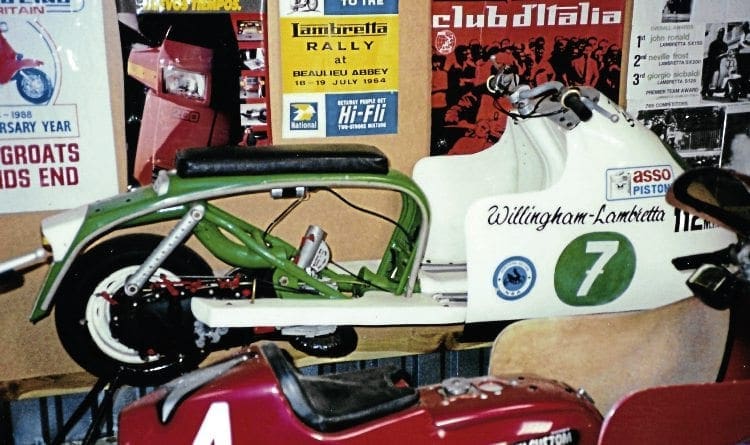

A 112mph, 250cc Lambretta, carving up sub-14 second quarter mile times with an ingenious rider on board. Fred Willingham and Peter Ham were pioneers of their time…

During the mid-1960s the fledgling sport of scooter racing began to gain momentum across Britain, soon attracting many Lambretta and Vespa riders to participate. It wasn’t long before a host of shops and dealers began to cater for the growing market. Arthur Francis, Roy’s of Hornchurch and many others offered tuning and aftermarket accessories to improve the performance of customers’ scooters. While many owners opted to use a shop to carry out the work, inevitably some would attempt do it for themselves.

Drag Fest

In 1964, a group of American racers came over to Britain to promote the sport of drag racing, more commonly known as quarter mile sprinting, with a series of demonstrations known as Drag Fest. In attendance was a young teenager from Bradford by the name of Fred Willingham. Initially, he took little interest at the proceedings, but once he was back home, the thought of tuning his scooter to make it go faster soon changed his mind. Though Fred competed in one of the 24 hour reliability trials at Snetterton race circuit, the idea of track racing didn’t appeal to him.

Remembering what he had seen at Drag Fest, Fred made the decision to go sprinting instead. Two wheeled sprinting in Britain at that time was run by the National Sprint Association (NSA). Dominated by supercharged Triumph and BSA motorcycles, the idea of a Lambretta joining the paddock seemed quite a novelty. Undaunted, Fred set about preparing his Lambretta knowing he would be up against bigger opposition from the outset.

Kneeler

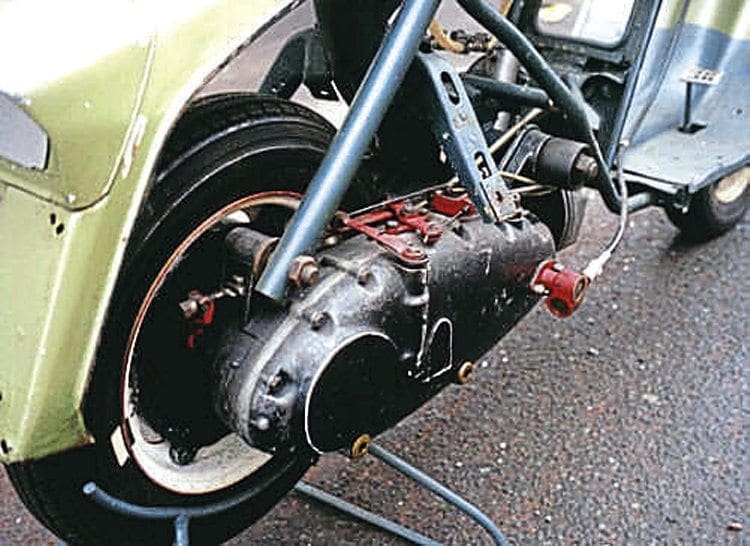

Having visited several NSA meetings and seen what other riders were doing, Fred opted to go for what is known as a kneeler layout. With the seating position directly above the frame and the handlebars attached to the forks, the rider lies less prone on the machine. Giving a much lower centre of gravity it allows the rider to pull off the line at greater speed without the problem of pulling a wheelie. Lambretta Concessionaires and Filtrate Oils had built a similar machine during the same period of time as they attempted a world record with their Atlanta 5 project.

Built around an old Li 150 costing a mere £5 and fitted with a TV 175 engine, Trip Trap as Fred named it, was born. For a first attempt it was pretty impressive and showed off some of Fred’s excellent engineering skills. In an attempt to create enough power the TV cylinder was extensively ported, Fred taking what guidance he could from the handful of books that were available at that time on two-stroke tuning. The engine would run on methanol which required a 16:1 compression, achieved by using a Villiers motorcycle cylinder head converted to fit. Using the rather crude Wal Phillip’s fuel injector system Fred took advice from the man himself to help set it up correctly. With an expansion chamber made by converting an Ariel Arrow exhaust the top end was complete.

At its first outing in 1965 to the astonishment of regular NSA riders it compared more than favourably, recording similar times to those of the class leaders. Fred intended to debut Trip Trap to the scootering population at the 1966 Isle of Man scooter rally. Despite all his preparation it never happened due to a ferry strike, causing the event to be cancelled. Not one to be put off, Fred returned there the following year where Trip Trap recorded a time of 16.5 seconds for the quarter mile. He not only beat all the opposition but with his clever engineering showed what lay ahead in the future. (see pic 1)

More power more reliability

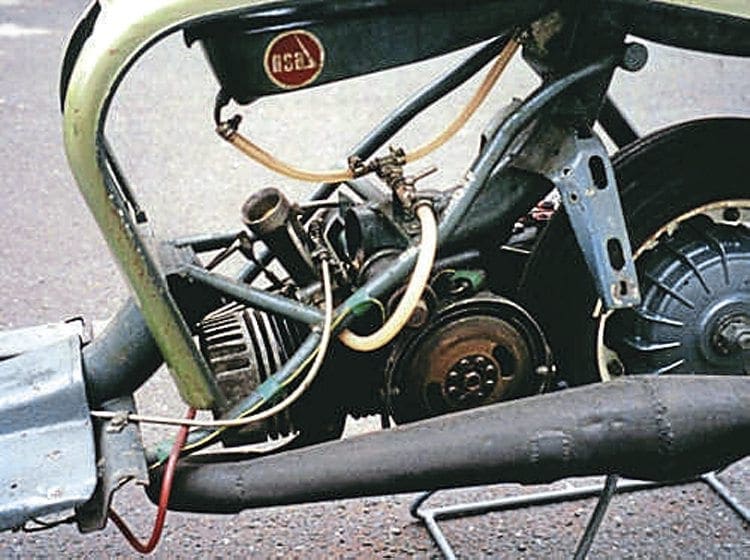

By now regularly competing in the NSA, in 1968 Fred decided to move the engine capacity up to 225cc. Having started to experience handling problems with the kneeler as well great opposition from other scooter riders because of its design, a change back to the orthodox Lambretta layout was made using a Series 2 frame. Over the next four years the engine would undergo rapid development which would see it become one of the most powerful Lambretta engines ever built up to that point in time.

Fred would base all development around the standard Innocenti 200cc cylinder, even though he would finally move to a homemade aluminium cylinder in his final years of sprinting a Lambretta. While all aspects of the engine would be developed it was the top end where most work would be carried out. Like anyone else who was attempting to tune a Lambretta cylinder at the time, the main obstacles were what you had to work with. (see pic 2)

The Innocenti cylinder had the available meat to be bored out to 71mm and though unreliable on the road due to the thin walls of the sleeve, for racing it was adequate enough. The problem lay in the choice of piston as the only real option was the Dykes ring

type. Though it was a two ringed piston, the top ring had an angled step which was in line with the crown. Problems arose when the exhaust port was enlarged, which in some cases caused the top ring to catch the port at higher rpm. This would cause the piston to shatter and result in terminal engine failure. It was a common sight at many race meetings as tuners widened the exhaust port too much in the quest for more power.

Fred’s answer in solving the problem was to bridge the exhaust port. Having seen it done by several manufacturers, most notably Bttltaco, the idea was simple enough. Though it seemed like a straightforward modification it didn’t come without its problems. Firstly it was an obstruction to the gas flow. Fred overcame this by making the port even larger now that it had the support in the middle. The other problem was the potential for the support to crack and break off. Though braised in to the steel of the cylinder, the support would be under constant stress as the ring rode over it, the only option being to constantly check for fatigue. The modification worked well and prevented the Dykes ring from failing while at the same time allowing Fred to get the larger exhaust port he needed to create enough power. (see pic 3)

In 1971, with the advent of larger capacity Japanese motorcycles becoming widely available, Fred had the idea to start using compatible components. The Kawasaki K2 750 was a triple cylinder two-stroke with each piston being 71mm in diameter. Using the same piston port induction the K2 piston was a compatible fit with only minor modifications needed. Not only did the piston have an orthodox ring layout, it was lighter and better made – allowing the engine to rev higher without any problem. By using the K2 750 piston Fred had the foresight to use technology outside the realms of what was deemed acceptable in the Lambretta world. (see pic 4)

By this time Fred was running consistent mid-14 second times for the quarter mile and over the longer mile distance achieving a top speed in excess of 100mph. He was virtually in a class of his own and as the completion tried to catch up he attempted to push the boundaries even further. However he wouldn’t take up the challenge unaided.

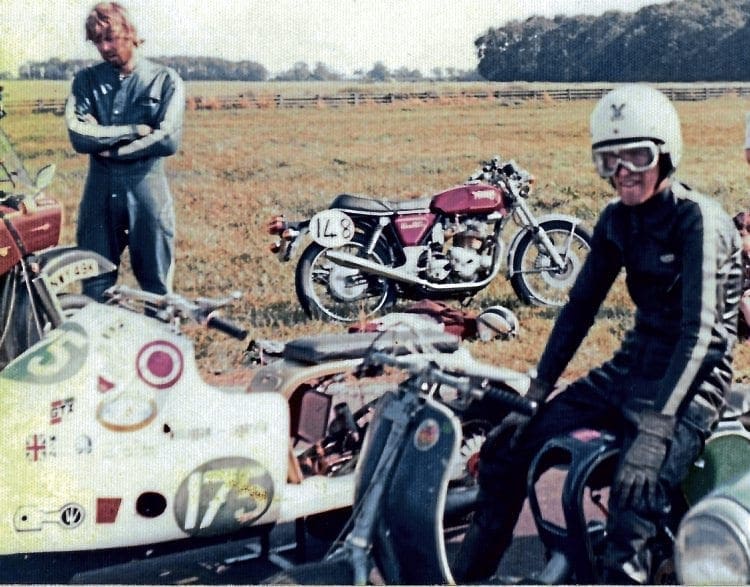

A little help from my friend

Peter Ham had owned a Lambretta for several years and like Fred had started sprinting regularly. Though he and Fred lived locally they didn’t get to know each other until a chance meeting at an NSA event. Soon they began to work on ideas together and would travel to meetings in Fred’s van. Peter was an RAF engineer and this gave him access to all the tooling and equipment they needed. As Fred once said: “Peter had the best workshop facilities available and it was all paid for by the British government.” Soon enough Peter took up many of Fred’s ideas and converted his cylinder to take the K2 750 piston. Using similar porting techniques he too would also achieve 14 second quarter mile times. (see pie 5)

Two heads are better than one

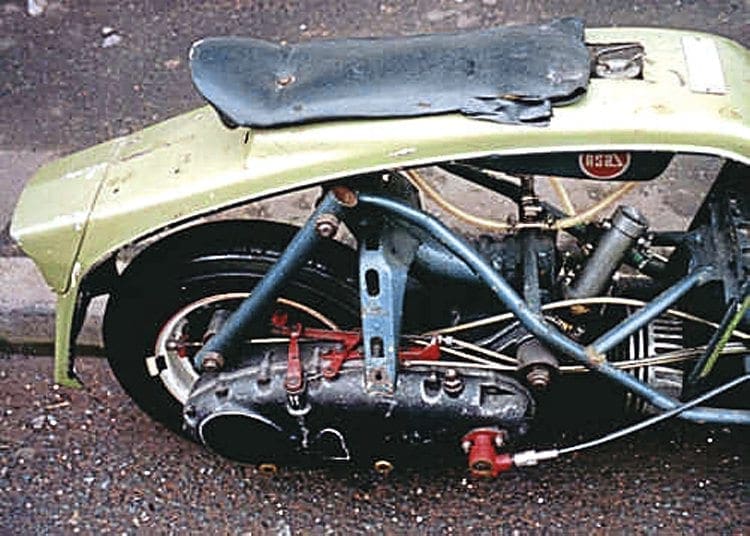

With both of them working on ideas together, development of their sprint machines accelerated at a fast pace. With the performance gained in the cylinder they developed a seven-plate clutch to cope with the power through the transmission. Extending the clutch basket and crown wheel to take the extra plates, at one point Fred used a nine-plate set-up. Though they didn’t use nor need a kick-start shaft it was still necessary to use a side case packer to make enough room for the plates to fit. (see pic 6)

Another clever idea, though this time only used by Fred was the drip feed oil system. A small tank was fitted above the crank case with three pipes which feed in to the top on the gearbox. On the start line he would feed a small amount of oil through the pipes in to the casing for it to complete its run with just enough lubrication. This helped reduced power loss through the transmission and gearbox area. Though not practical for road use it was still an ingenious idea and showed just how far it was possible to develop the Lambretta engine in the quest for more speed.

Probably the biggest and most radical development they undertook was direct induction. Not only would this create more power, Fred claimed this was the biggest improvement they ever made performance-wise, but it would also aid engine cooling as the fuel enters directly in to the cylinder. Though it sounded a good idea in practise it was impossible to achieve as the Lambretta main frame tube lies directly above the cylinder inlet. Innocenti had got round the idea by designing an offset manifold but this made the inlet tract rather long. (see pic 7)

While Fred had worked out how to bolt the fuel Injector directly to the cylinder and revise the port layout, it wouldn’t fit in to the frame. This is where Peter took over; he knew if that part of the frame tube could be removed the cylinder would fit. Using his engineering skills he came up with an ingenious solution. Having removed the section of the main tube required, he then created a triangulated framework around it to support the removed section. By using the triangulation theory this gave the frame great strength and stopped it collapsing once a section was removed. It worked perfectly and both he and Fred adopted the idea on their machines. Now Fred had ample space to fit the fuel injector where he needed with immediate results in acceleration and power increase. (see pic 8)

By combining their skills and working together they showed what could be achieved. Now working as a team they could keep up with the development needed to stay ahead of their competitors.

The final boundary

During the early part of the 1970s, as both track racing and sprinting grew even greater among scooter riders, Fred and Peter pushed the boundaries even further. Peter with his standard Lambretta layout would achieve a personnel best time of 14.8 seconds for the quarter mile while over the mile distance record a speed of 97mph. He sprinted his Lambretta until 1980. (see pic 9)

Fred though would go on to achieve even greater things. Having adopted a full front fairing, getting the idea from the bigger motorcycles sprinting in the NSA, he now had a more streamlined machine. A final chassis was built using a Series 3 frame which still attracted protests among some riders as to whether or not it actually was a scooter.

As a tongue in cheek response Fred fitted a rear light unit to the frame. It served no other purpose than to remind people it still was a Lambretta however much it had been modified. Now running a homemade aluminium cylinder the capacity of the engine was raised to 250cc. At a sprint meeting at Fulbeck in 1972 he would complete the quarter mile in 13.95 seconds. Not only the first Lambretta or scooter for that fact ever to go under 14 seconds over a quarter mile but a time that took over a decade to beat. (see pic 10)

Not content with this over the mile distance, he would achieve a top speed of 112mph – a feat only a few Lambretta riders have surpassed more than 40 years later. By 1973 Fred knew he had developed his Lambretta as far as possible. Still keen to go sprinting he made the move to motorcycles and at one point held several national and world records. He retired from sprinting in 1980. (see pic 11)

Legacy

While there have been many great Lambretta tuners, Fred Willingham and Peter Ham were early pioneers. Their radical and revolutionary ideas can still be seen on some of today’s Lambretta engines. Though they didn’t have access to modern tooling facilities they still managed some great engineering. (see pic 12)

During the early 1970s, Fred Willingham wrote several articles on the subject of how to tune a Lambretta engine and build a sprint bike in Scooter World magazine. He then went on to be the magazine’s technical editor until it finished in 1973. These articles are highly recommended and full of useful information even today. If you get the chance to get hold of a copy they are well worth a read.

Stu Owen

This article was taken from the June 2016 edition of Scootering, back issues available here: www.classicmagazines.co.uk/issue/SCO/year/2016