Development of the Lambretta engine is a continuous cycle but in the early 1990s one such creation completely blew the opposition away… the cooler.

Conditions were ideal for racing on that day in the spring of 1990, the weather warm and sunny, the track surface the ideal temperature. Three Sisters race circuit in Lancashire was ideal for the spectator too as you could see virtually the whole track wherever you stood. With a host of different classes and three races over the day in each one, the action was frenetic from the outset. It was the first race in Group 6 that got everyone’s attention though. A matt black painted machine not only took the lead, but left the opposition in its wake. Its power out of the corners was immense; all of us witnessing a truly ground-breaking performance. But what was it?

Chip break

Scooter racing at that time was at its peak with around 400 licence holders and grids in every class full. The competition was fierce and none more so than in Group 6. This was the group where riders had much more freedom over their machine as the rules were not as strict. It had led to both frame and engine development accelerating at a rate of knots, even more since the introduction of the TS1 kit to the fold two years earlier. There were problems beginning to arise with many of the big Group 6 engines as the power they produced significantly increased. The main weak point was the crank which quite often couldn’t take the power produced, resulting in an expensive blow-up. If this wasn’t enough to deal with there was also the issue of overheating. Engines would perform perfectly at the beginning of a race but as they wore on many would overheat and lose power or worse still, seize. Both areas would need addressing but doing so wasn’t as easy as it looked.

Con rod conversions had been around for quite some time which helped prevent them snapping, certainly in high revving engines. Even so, the problem of cranks twisting was most concerning and if it was violent enough then even the strongest con rod was prone to failure. When it came to water cooling, that too had been around for some time. It was still in its infancy though as the work required to put a workable system on a cast iron barrel was considerable. With the advent of the aluminium cylinder in the TS1, this was now much easier to achieve and there was a much bigger scope for what you could do with the transfers to create even more power.

The Leicester Lambretta race team (LLRT) had seen great success within scooter racing, most notably because multiple British champion Dave Webster was a major part of the team. Not only was he a very talented rider but also one of the country’s top tuners. When it came to the standard groups there was only so much you could do to the engine and the rider’s ability played a major part in winning. Though Group 6 still relied on rider ability, if a significant advantage in the engine department could be made then this would be a huge bonus.

One of the team’s riders in Group 6 was Guy Topper — a tall thin lad but one with an excellent engineering background. It was during the chip break one Saturday in the team’s headquarters that he and Dave Webster first discussed the idea of a new machine that would become known as The Cooler. It would, of course, feature full cylinder water cooling but also incorporate a much bigger and stronger crank. Dave Webster was the driving force behind ideas like this but input from other team members played a significant part in making it all happen. Without hesitation, the idea was put into practice but it would require a major feat of engineering the likes of which had never been seen among the Lambretta ranks.

Solve one problem, create another…

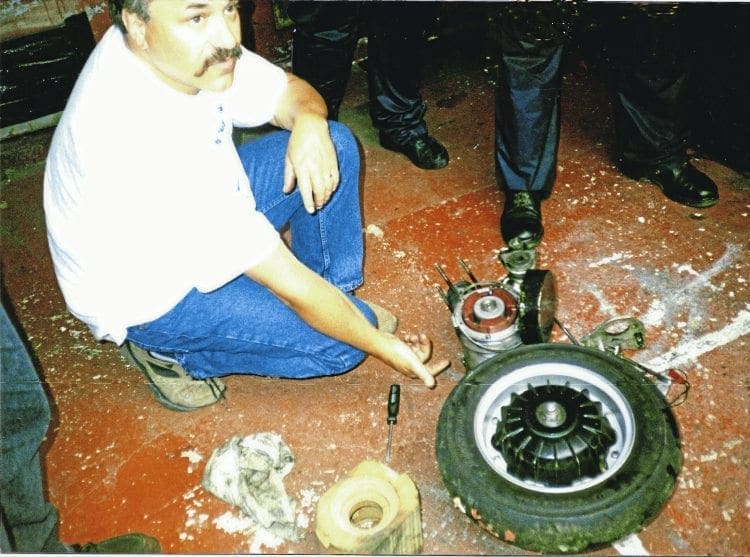

Dave started off by meticulously drawing up plans and dimensions for the top end of the crankcase. With the crank at the heart of things that needed to be sourced before anything could go ahead. By chance, he had come across a second hand one in a motocross shop from a Suzuki RM 250. Upon closer inspection, he decided this is what they would use if it could be made to fit. With its much more robust build he was sure the problem of crank twisting would be eliminated and become a thing of the past. Though there would need to be some modifications to the crank, in essence, he had found the perfect choice.

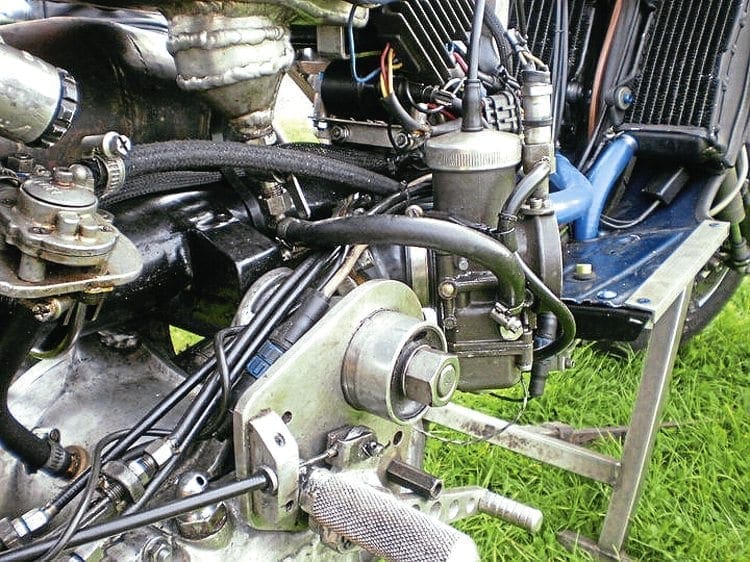

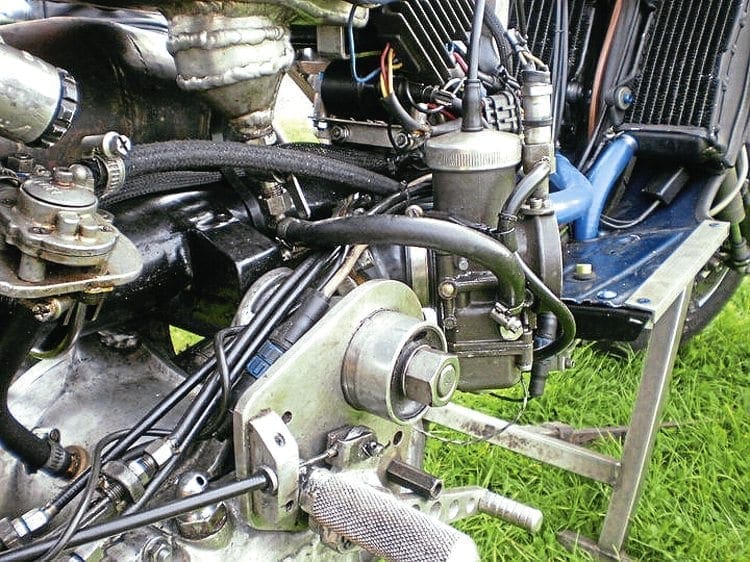

The next issue was that of the stroke which would need to be significantly increased. The Group 6 class limit was 258cc so the idea was to get it as close to that as possible, allowing for a few oversizes should the cylinder need reboring during its racing life. Here lay the next problem though — getting up to the required capacity was usually done by boring the cylinder out to take a bigger piston, for example between 72 to 73mm. Doing it this way meant the area for the transfers is greatly reduced as there is only so much room between the stud spacings. Though Group 6 did have more freedom in its rules there was still a set to adhere to and moving of the stud spacings was strictly prohibited. Dave worked out if the bore was smaller but the stroke increased the capacity required could be reached. At the same time, this would give more room for transfer area, thus allowing for more power.

The idea was fine but the stroke would need to be raised to 70mm, way over the original 58mm that is normally fitted in a Lambretta crankcase. To fit the longer stroke would mean machining the inside diameter of the casing to allow it to fit in. If it was machined out that far, the casing would be as thin as paper — making it too weak and probably cause it to collapse. The solution was to weld up the back of the casing around 10 to 15mm deep all the way round to allow for the machining out. This alone was a mammoth task and one likely to cause distortion of the casings and even possible failure.

The worry was all this could be done and the crank not fit despite all the drawings. Guy came up with a solution by making a mock-up of the crankcase mouth from a block of wood to the dimensions Dave had drawn up including a wooden mag housing. The crank fitted perfectly in the mock-up so they went ahead with the welding work, a unique and simple solution to solving the problem.

Having spent several weeks working on it the casing was ready to be machined out to take the crank having been back and forth to the welders many times during that period. Once done the next problem raised its head — it was one step forwards but several backward. The heat of welding the casings up had distorted the main bearing housing so much the bearing itself wouldn’t fit. This had to be bored out and eventually a smaller spacer fitted to allow it to sit perfectly. As one problem was solved it just created another like a vicious circle but both Dave and Guy were determined to succeed.

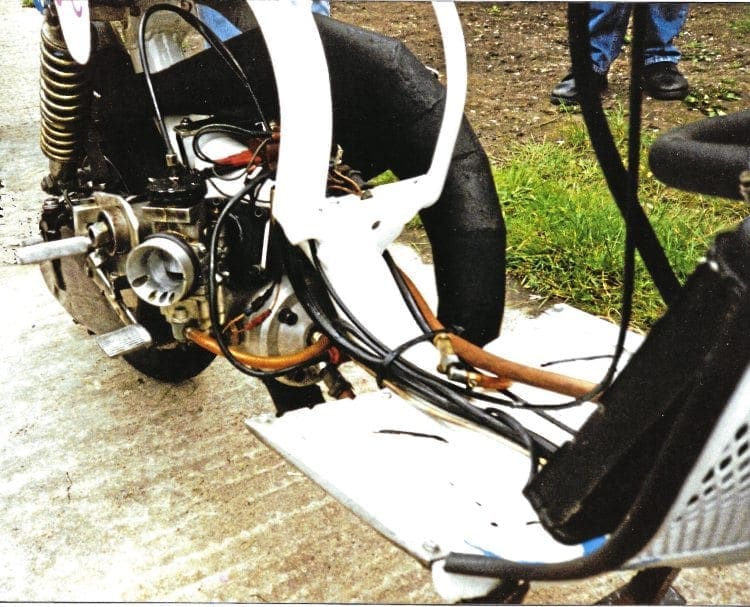

Finally, they got everything to fit so the focus of attention now switched to the barrel. Dave had originally done the water cooling on Norrie Kerr’s LC engine so this was adapted to what he was going to do. Eventually with the porting work finished it now not only incorporated huge transfers but also a much larger reed block induction. This was also helped by an extra induction port into the top of the crankcase. If the engine worked right it would create an enormous amount of power and torque at the same time. To allow for seizures, not that they wanted any, the barrel was steeled lined which was far easier to clean up than if it was Nikasil plated. The piston was out of a Yamaha, the con rod from a Honda and the crank from a Suzuki. All Japanese and a right mix of manufacturers but if the combined components worked in harmony then what did it matter?

The day of reckoning

After 10 weeks of intense labour ‘The Cooler’ was ready to go. It would make its debut at Langbaurgh race track near Middlesborough in April 1990. Surprisingly, there were no initial teething problems, as Guy said: “It all fitted together and the technology was nothing new.” Norrie Kerr was on hand to make sure the water cooling worked perfectly and it finished all of its races at that meeting. What would take more time was getting used to riding it and understanding its power characteristics. Guy is a tall lad and never looked comfortable on a Group 6 machine at the best of times.

The gearbox had been designed around the engine’s big torque and power spread and used a tall first gear. Though it may not pull away well first gear was only used to get going so it was the other gears that were more important. Using a Spanish Pacemaker gearbox was the perfect solution as it was stronger so could cope with the extra power. Both the power delivery and gearbox choice would take some time to get used to but it was clear to see its potential from the outset.

To compound matters even more, Guy was getting over a broken arm and wrist that year. With many of the tracks being tight and twisty he found the going very hard. This wasn’t helped by the fact there were some good racers that season — many of them used to their machines whereas Guy was still learning the traits of his. As the season continued the successes started to come as he began to win races and if not was in the top three. The reliability that they had hoped for had also materialised meaning that there were no breakdowns and as the saying goes, to finish first, you must first finish.

By 1992, Guy was on top of his game and seasoned at riding ‘The Cooler’ to its true potential. This would lead to him winning the overall championship in 1992. It was an achievement of great pride not only because of his riding skills but also through the creation of such a great racing machine. Though a lot of the ideas and work came from Dave Webster much of the input was from Guy and others within the team and all were proud of what they accomplished. At the end of that season Guy packed in scooter racing and after just three seasons the machine would now become idle, an ornament in the MSC showroom.

Not going to waste

Mark Ellis had been racing in Group 4 for a few seasons and would frequent MSC most Saturdays. On one such visit, Dave Webster asked Mark if he would like to have a go on The Cooler, hinting there was a race looming at Brands Hatch. This was 1996 and the scooter had been redundant for the last four years, but the lure of a championship winning machine was too tempting. It was a big step up from what Mark had previously known and a steep learning curve.

After a quick practice session, it was apparent just how much power it actually had. Combined with handling superior to that of any Lambretta he’d ever ridden, Mark declared he was ready to race. Unfortunately, on the first corner he was shoved off the track and by the time he had rejoined was in last position. There was nothing to lose so with a fistful of throttle he proceeded to make his way through the field not only finishing a respectable third but also setting the fastest lap of the day.

As the 1997 season loomed, Mark persuaded Dave and Guy to let him race The Cooler that season. This agreement carried on till 2000, some three years later. Though Mark was allowed to change brake and suspension settings, the engine was a ‘no go’ area. It must be remembered that the engine was seven years out of date compared to what was now on the track, so chances of winning were slim. Despite its ‘aged technology’ he was still a front-runner, regularly finishing in the top positions every race. Mark recalls: “The Cooler lacked the top-end speed of our rivals.” Group 6 was ultra-competitive and the likes of Stuart Day had a 10mph advantage on the straights. Even so, Mark finished second overall two years running in the Group 6 championships, proving how good a rider he was and that The Cooler was still competitive. By 2000 Mark had switched to racing motorcycles and handed it back to MSC where it would spend a few years gathering dust.

Both out of retirement

In 2008 Guy was looking for a new challenge and decided to get The Cooler out on track. This wasn’t as easy as it first seemed; Mark had crashed it at Mallory in his last races and though the frame had been fettled, it still wasn’t straight. The first step was to get the frame true and Guy said it took a while to get the handling back on par. Then there was the engine. It had been doing the rounds for 20 years by now so was in dire need of rebuilding.

Guy’s return to the track coincided with a resurgence in scooter racing. To have someone like him back out on track along with one of the most iconic race machines was a welcome boost to say the least. Once happy with both the handling and engine reliability he soon began to show a new generation of racers just how good he was. Though the technology was by this time outdated that didn’t seem to matter as Guy was a regular front-runner. It wasn’t until 2010 that he was attending every meeting and in 2012 he once again became overall champion exactly 20 years after he had originally done it. An accolade I don’t think any other scooter racer has ever achieved.

Never to be seen again

When Guy Topper and Dave Webster first built the machine, a Lambretta engine like this, both in terms of technology and performance, had never been seen before. The challenges and engineering skills to create it were truly immense and even all these years later one wonders how they ever pulled it off. These days it’s far easier to produce an engine with the same sort of performance with far less effort. ‘The Cooler’ was ground-breaking when it was first introduced and more than likely responsible for how Lambretta tuning shifted direction at that time. It will be always remembered in the history of Lambretta performance as one of the greats.

Words: Stu Owen

Photographs: Thanks to Guy Topper, Jaime Prat de Salomone and Mark Ellis