During the mid-1980s, scooter tuning was often less about outright speed and more about sound, image and the feeling of performance. In a reflective new column, Stu Owen looks back at an era when expansion pipes, noise and perceived power defined the tuning scene — even when the speedometer barely moved.

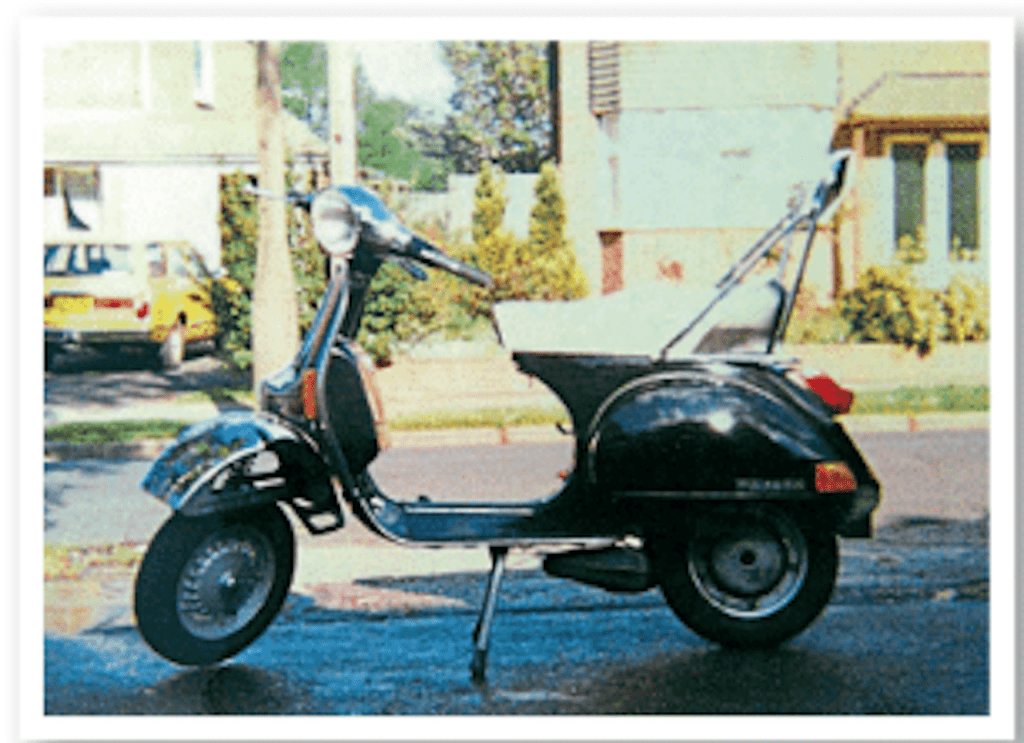

Writing as part of Scootering magazine’s 40th anniversary preparations, Owen revisits his early scooter years and the naïve enthusiasm that characterised the period. His first scooter was not a Lambretta, but a brand-new Piaggio PX125, chosen not for its tuning potential but for its reliability. Starting first or second kick without fail, the PX125 delivered exactly what young riders needed: dependable transport and freedom, regardless of weather.

Once the engine was fully run in, riding habits quickly changed. The throttle became an on-off switch, and with no real benchmark for comparison, the scooter felt fast enough. Against everyday cars of the time — such as the Mini Metro or Vauxhall Nova — the PX held its own, even if it struggled to match more powerful machines like the Astra GTE or Ford Capri. For a while, reaching close to 60mph felt like plenty.

Enjoy more Scootering Magazine reading every month.

Click here to subscribe & save.

As familiarity bred ambition, the desire for more power inevitably followed. But with that came a dilemma familiar to many riders of the era: was extra performance worth sacrificing reliability? Owen recalls a local rider who fitted a 175cc kit and larger carburettor, achieving impressive acceleration but suffering frequent breakdowns and seizures. Inexperience with setup rather than flawed parts was likely the cause, yet the constant mechanical failures were enough to put many riders off engine tuning altogether.

Instead, attention turned to a simpler and seemingly safer upgrade: the exhaust. The standard PX exhaust was visually awkward, sounded weak, and drew mockery from motorcyclists. Replacing it with an expansion pipe felt like an obvious solution. Costing roughly a week’s Youth Training Scheme wages, fitting the pipe instantly transformed the scooter’s appearance and, crucially, its sound.

In reality, performance gains were minimal. Acceleration felt marginally sharper, but top speed remained unchanged. Despite attempts to extract more speed — including full-throttle downhill runs — the speedometer rarely showed any meaningful improvement. The uncomfortable truth was that a quarter of a month’s income had been spent without delivering real speed.

What the expansion pipe did provide, however, was noise. The transformation in sound was dramatic, replacing the factory exhaust’s hairdryer-like note with something that felt closer to a motorcycle. The increased volume created the illusion of power, drawing attention on high streets and at bus stops alike. Riders might not have been faster, but they certainly sounded like they were.

The column captures a defining aspect of 1980s two-stroke culture. Just as Japanese motorcycles could be heard long before they arrived, tuned scooters became part of the same soundscape. Speed was often secondary to presence, and the noise itself became the performance upgrade.

Looking back, Stu’s reflection highlights how scooter tuning culture has evolved. What mattered then was not lap times or dyno figures, but image, sound and the feeling of being fast — even if the numbers told a different story.

Original Stu Owen article appeared in Scootering Magazine June 2025 issue. To subscriber for more great stories like ths please visit https://www.classicmagazines.co.uk/scootering