After negotiating the 106mph ‘Bora’ winds of Trieste and the rolling vistas of State Road 58, Christian meets up with Grand Prix track marshal Fedele for beers, memories of 500cc GPs in the 1980s and a spin around the historic race track on his ‘negra’ Vespa.

The walls of Trieste, a port in north-eastern Italy, are familiar with the strong winds that surge in off the Adriatic Sea. The gusts can rattle windows and shake roof antennas, just like trees during an earthquake. There’s one distinctive blast — the Bora wind which is particularly unpredictable, ferocious and dangerous. It slams through the city streets, testing the local population’s physical and mental stamina.

Enjoy more Scootering reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Blowing over from the Balkans, the Bora rages with a sudden hostile intent and the potential to hurl unsuspecting pedestrians to the ground with its violent gusts. Those who live in Trieste have learnt to defend themselves from this force of nature by acquiring a deep knowledge of the smallest and most sheltered alleys within the city. Using these narrow passageways as trenches, Triestinos avoid the strongest whips of wind and can seek refuge from the torment. The locals say that a Triestino (someone born in Trieste) is only a ‘real’ Triestino if he can continue to shop and go about his business along the city’s streets while the Bora is howling around him.

The Bora’s existence can be partly explained by the natural shape of the city and the fact it sits in a west-facing valley, which forms a channel for the wind that surges inland from the Gulf of Trieste. This formation encourages the prevailing winds to unload their tremendous power at up to 106mph on Trieste and its inhabitants.

Riding through Trieste is something else and trying to manhandle a Vespa through the Bora is an interesting experience to say the least. Planning a ride through the Gulf of Trieste towards the Balkans during the months of April or May requires some careful preparation and if you are thinking of mounting your windscreen for some classic touring — think again! The sheer force of the winds will make any screen mounted on your Vespa prone to damage, with cracked mounts being the least of your worries.

At worst, it could leave you with broken bits dangling from your ride while you are attempting to conquer some of the most dangerous Balkan roads.

A Trieste-based navy colonel, accustomed to the aerodynamic flows of the area, gave me some useful riding advice for handling the Bora winds: “The position of luggage must be checked frequently during a windy ride.” He suggests politely that I position all of the available weight between the rider’s legs and on the front rack, moving the centre of gravity nearer to the lighter part of the Vespa, thus planting the bike more firmly and evenly on the road. The riding position must be changed too, with the rider leaning a little to the front, and it’s best to wear snug clothing to allow the natural flow of the wind around the rider’s body.

Recently my trusty Vesap steed ‘Negra’ and I found ourselves confronted with the powerful wind that forms the Bora while riding towards the Croatian coast. By chance, on the day of my departure, the Bora blew to gusts of 75mph among the streets and I found my Negra turned upside down, still chained to a security pole on the pavement. Luckily she was still intact.

For those who decide to visit the Istria peninsula in Croatia via Italy, the best and maybe safest route is to follow the Trieste-Rijeka main road. Be careful though, the Bora can descend at any time.

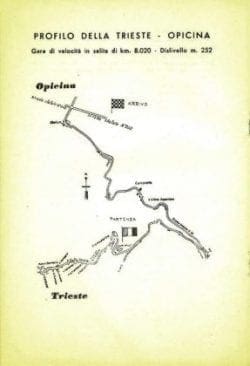

While in Trieste however, I recommend a run up the tarmac on the historic Trieste-Opicina hill climb originally known as the ‘Uphill Monza’. It’s an 8km-long track located 252m above sea level. From Piazza Dalmazia (the official starting point) the circuit makes its way down a series of plain turns which introduce the first climb. It then follows the Fabio Severn that slips past the university on the left. A brutal left hairpin pushes you onto State Road 58.

From this point the trail becomes a panoramic splendour and furiously pursues another series of turns until you reach the obelisk that signals the end of the track. I putter along this road on my Vespa where cars such as Alfa Romeos, Bugattis, Ferraris and Porsches have beaten each other to get their hands on the cup. I slip through the Trieste-Basovizza road and pass the Italian border, traversing a boulevard that brings me out onto the countryside.

Exploring the Istria peninsula, Italian territory before the Second World War, has been an ambition of mine for almost three years. Roads twist along the Classical Karst plateau (made up of weather-resistant rocks formations), squeezing the rider between rocks and ranges in a regular rhythm of rise, fall and sweeping turn. Even though the Istria peninsula is now under Croatian control, a strong Italian core endures in this country, lending it a bilingual culture that has persisted since medieval times and still survives today among the ‘old fellas’. While the number of English speakers is growing, you can easily speak Italian with many of the country folk and towns people. It’s not unusual to meet shepherds who spent time in Italy during the construction boom and who are still bilingual.

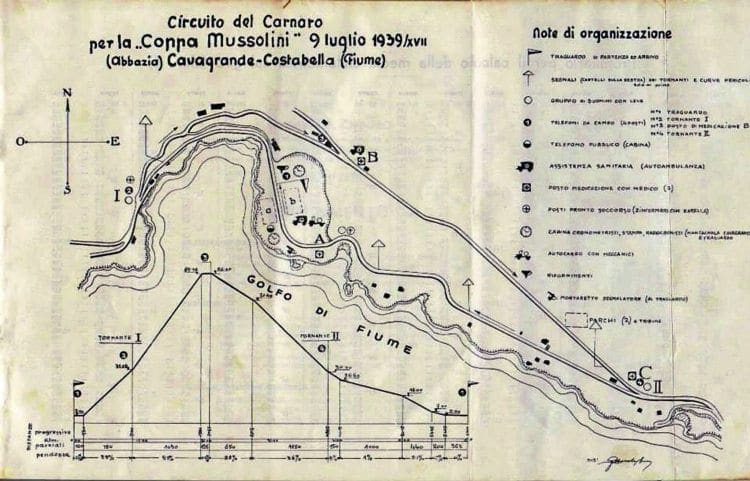

The Bora winds of Trieste are not the only record-breakers in this region as far speed is concerned. One of the most fascinating and dangerous race tracks, the Carnaro Circuit (later the Opatija Circuit) became renowned as the home of the Adriatic Grand Prix and shared an affinity with the Monaco Grand Prix. Built on a hill with steep climbs and sweeping bends, including two first-gear hairpin corners, the Carnaro became notorious among the racing fraternity.

The Camaro or Opatija Circuit has always intrigued me. I have always wanted to explore those straightaways and turns that stole the lives of a young riders including Briton Billie Nelson in 1974. His Yamaha hit straw bales near the U-turn and he was thrown from his machine, ending up in the crowd on the other side of the barrier. He died days later in hospital from his injuries. Some spectators were also severely injured in the crash.

Winds pummel me from right to left and in the opposite direction fully-laden lorries are heading to Trieste from Croatia and further south, bringing their own gale force air movements that serve to disrupt my balance. It’s like being in the ring with Lennox Lewis. You don’t know when the hits are coming, but you know they are coming. The classic cruising performance of a Vespa is totally compromised in these weather conditions.

Villages near the Italian/Croatian border look like ghost towns and as I pass by I cannot find any Konobas (Croatian taverns) with a functioning fireplace. Securing a shot of caffeine at eight o’clock in the morning becomes a necessity. I reach the Croatian border after a solid two hours behind the bars but I realize I have only covered 35km. As the border disappears in my mirrors, the road changes and dives gradually towards Abbazia, the famous race track. As the signage changes, it seems I have been blessed with good fortune. The boiling rage of the prevailing wind settles down to a simmer and stops threatening to slam Negra and I into the rock wall we have been following to reach our destination.

As well as being famous for its gusty winds, the Istrian hinterland of Croatia is famous for its truffle dishes, so as I enter a typical Konoba, I try my luck and order the ‘fertaja’. A Croatian lady dressed in traditional style complete with head-kerchief gazes at me thoughtfully from behind a wooden table. She professes to be the former chef of the hotel and explains the process of cooking and serving truffles. “You have to know the chicken who brooded the eggs and the dog who sniffed the truffles. If you trust in them the dish will be outstanding,” she says, with a hint of a smile.

Despite the tavern having humble furnishings the chef dresses my meal grandly with a flurry of truffle and a delicate sprinkling of crushed nuts.

I dig in with my fork like a biker who has been driven half-crazy by headwinds all day long, but in that moment my haste is suddenly forgotten as the jubilant scent of truffle perfume fills my nostrils. I savour the warm earthy colours of the dish, glowing yellow and brown, before I am off once again, devouring the whole richly flavoured meal in less than five minutes. As I exit the Konoba, I realise that the Bora has wiped away all the grey clouds from the sky, and a warmish spring sun has appeared. Everything seems refreshed and renewed now that the wind has passed.

The street vendors along State Road 8 rush to light the fires they use for grilling meat and I feel now that I can truly relax and pay more attention to what is passing by as I glance out from the side of my helmet. The main road that takes you to Rijeka crosses from west to east. Soft turns lead my little Negra’s wheels up to the entrance to Abbazia — a city known for its heavy tourist flow, luxury hotels built by the 19th century Austrian kings and now the modern wellness centres you can find dotted along the seaside.

Its two main streets merge at a local peak so travellers looking towards the Adriatic sea are rewarded by a spectacular vista and its rich shades of blue. Continuing towards the city centre, the sloped streets bring you out just in front of the Rijeka-Pula bus stop — a central location and meeting point.

At this corner I meet Fedele, a gangly man in his 80s who smokes a pipe under his yellow cap still ‘sponsored’ by Yamaha. I met him during one of my last rides in the city and after a couple of beers we became friends. He has a great knowledge of and love for Opatija and it seems he is one the few former track marshals still alive who can share the Abbazia/Opatija city circuit thrill from many moons ago.

“Mussolini wanted this Grand Prix,” he says, lighting up a pipe that is almost completely black from years of ash abuse. I remember when engineers visited the city to measure the roads and sketch the first idea. At the time I was working as a blacksmith, pounding my hands for 15 hours a day.” We order a Pivo in a pub near the old corporate box area. Fedele sits on a wooden bench with his back facing the Fiume Gulf.

His memories of racing and action and crashes on the once famous Grand Prix Circuit take me back in time to its opulent heyday. “The Carnaro Circuit, later known as Adriatic Grand Prix, was developed along the Preluk coast road. It’s made of two really narrow hairpin turns and a 100m vertical hill climb,” he says. “As the bikes would reach the peak’s summit, they were pushed to the limiter until hairpin number two. Then came a frantic stop, then a right bank and off they went again. Following the last descent, the track turned before the finish line.”

Fedele remembers finding the right gearbox set-up for this track was tough: “Going fast during both the hill climb and the descent was totally impossible.”

Fedele takes a long pause between the puffs of his pipe and with a solemn voice remembers: “In 1974 Otello Buscherini was disqualified after his 125cc first place victory. It was a technicality — the officials noted that his Malanca had seven gears instead of six as required in the regulations.”

As I listen to Fedele reminisce, I scan the road and from where we stand I can see hairpin number one. I imagine the roar of the motors advancing those turns and the drum-brake-whistle accompanying the frantic down-shifting. It seems Fedele can read my mind.

“It was one of the most challenging circuits in the Adriatic area but it claimed too many riders,” he says. “In 1977, the track was closed after numerous boycotts by riders due to safety concerns. The track was ultimately closed down and moved to the newly built Rijeka circuit famous during the heyday of the World 500cc GPs of the 1980s.” As Fedele ends his lament and as if on cue, the sky turns grey and the winds return, forcing me back to the present.

With Fedele’s approval and his recollections fresh in my mind, I am encouraged to toss the Vespa along this historic circuit/road. After a lengthy warm up — both me and the bike — I give it a go and clock a hefty 14 minutes 55 seconds, give or take. In 1973 Kent Andersson, aboard his Yamaha 125 machine, snatched pole position with a two minute and three second lap time around the 6km circuit. Looks like Negra and I may need a little tune up.

Words and photography: Christian Giarrizzo

This article was taken from the May 2016 edition of Scootering, back issues available here: www.classicmagazines.co.uk/issue/SCO/year/2016

Enjoy more Scootering reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Scooter Trader